The assignment was clear enough. Select a manuscript of interest from Bryn Mawr’s Rare Book and Manuscripts arm of Special Collections and conduct a deep investigation into the history of the book itself. Yet as Joshua Shaw (M.A. Candidate, Classics) was quick to realize, there is much more to learn about a book than the words authored onto its pages. Through careful study and the aid of ultraviolet photography, over the course of the semester Joshua would unravel the mysteries of a 19th century manuscript fraud practice.

The project was the final for “Forming the Classics: From Papyrus to Print,” a unique course co-taught by Classics Professor Catherine Conybeare and Eric Pumroy, Seymour Adelman Director of Special Collections. Here students learned the methods of textual history research and the paleography (the study of handwriting), book production, and manuscript transmission – through hands-on experience with texts from Bryn Mawr’s Special Collections archive of 60,000 books and one million manuscript pages.

Joshua chose Manuscript #4 of the Gordan family collection on loan to Special Collections. The book was thought to have been compiled in the 15th century and contains the writings from the ancient Roman author Cicero, among others, meticulously copied by scribes. Cicero is the subject of Josh’s Master’s thesis and so Josh felt that investigating this book’s production and collecting history would be an excellent chance to look at his thesis topic from a different perspective.

Manuscript #4 came to America in the early 20th century and has been in the private collection of the Gordan family since 1930. The Gordan family has since loaned it to Bryn Mawr. Between 1849 and the 1920’s the book was sold up to six times. The number of sales in such a short period of time reflects a period when public interest in pristine manuscripts was high, especially those from classical antiquity. It was during the second half of the 19th century that some of the most spectacular archaeological and paleographic discoveries were made, meaning that finds from the past were a regular blockbuster feature of the world’s major newspapers. This not only drove the interest of the public, but also eager antiquarians and collectors – and the con artists who sought to defraud them.

Josh would soon find that Manuscript #4 was not what it claimed to be. An inscription on the book’s inside cover declared that the book was from a famous scribal school and monastery in Padua, Italy – neatly confirmed by a still extant catalog from that same archive dating to 1453. Josh was able to determine that the book’s history was not so clean. Its inner vellum leaves, scrawled with the words of Rome’s most illustrious statesmen, had fallen victim to a con-man’s ruse in the 19th century in an effort to profit from antiquarians who craved original, old, never-before-seen manuscripts for their own private book collections.

Before his discovery, Josh was somewhat unimpressed with his selection. At a glance, the book seemed to lack any of the flashy or strange attributes that for bibliophiles and paleographers make seemingly mundane manuscripts exciting for study, such as interesting comments in the margins, known as marginalia, or even a unique scribal hand. However, Josh quickly began to notice that a few things did not add up. For one thing, the titles of Cicero’s paradoxa Stoicorum (“Paradoxes of the Stoics”) were written in Greek, whereas the body of the texts were in Latin. Josh already knew that knowledge of Greek was very rare before the end of the 15th century (the first Greek professor came to Padua University in 1469). Manuscript #4 was therefore either suspiciously anachronistic, or a very early testament to the scribal copying of Greek – a find which would have been truly remarkable.

To query the book’s authenticity Josh turned to the book’s front inside cover. Here the book features several pasted and handwritten notes that suggest the book’s ownership history. Each note was a written intervention that prior owners had made to either confirm their possession of the book, or to physically affix provenance information they knew to declare its authenticity.

The accession history had previously been investigated in the 1990’s by former Bryn Mawr graduate student Kathleen Whalen (M.A. '90, Greek). One note says that a previous owner had brought the book to the William Fitzgerald Library librarian at Cambridge University, who in the late 19th century had determined that the book came from the archive at the Padua monastery. For the book’s early owners, a seemingly genuine Ciceronian manuscript from such a well-known archive was a financial asset. The book’s provenance could be traced to its moment of creation and the notoriety of the Padua archive across Europe gave the manuscript the sort of historic flare that tended to excite collectors.

“In manuscript studies, provenance is everything,” says Josh, “This is often the first principle on which many other important observations rest. If you can find out when and when it came from then you can make sense of many of the other pieces.”

The Padua monastery was famous as a center for the training of church scribes. These schools were responsible for the training of professional scribes and copyists, so scholars often come across the practice texts of students who painstakingly would copy and rewrite well known texts to perfect their penmanship. The seemingly mundane copy work of these students is the reason why so many ancient and Medieval texts survive into the modern day.

It made sense that this book was from a scribal school. Manuscript #4 is clearly written by a number of different individual hands – the telltale mark of an army of eager early professional scribes. Yet Josh kept coming back to the inscriptions on the front cover. The anonymity of the notes meant that the motives of their authors deserved further scrutiny. He would soon come to realize that some notes were erased and chemically altered – a practice consistent with 19th century forgeries and falsified manuscript provenances.

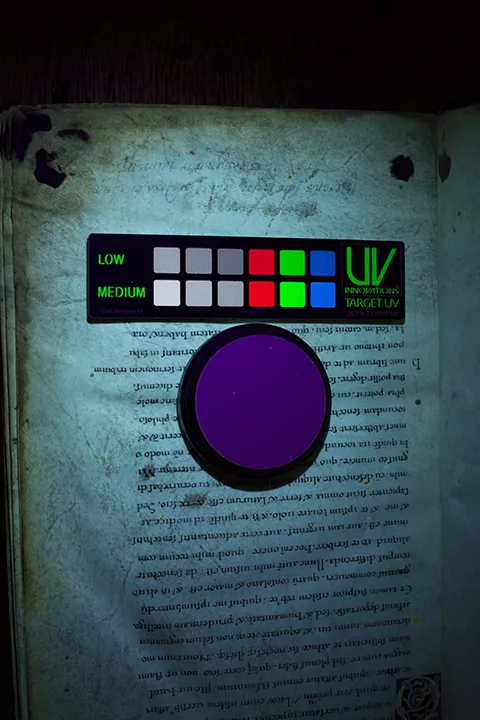

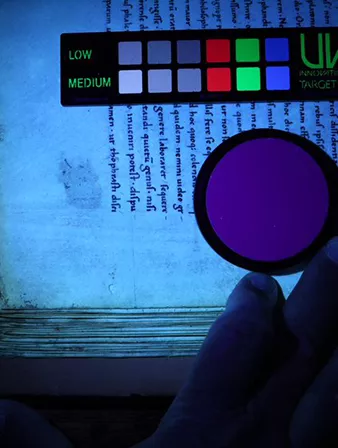

This revelation afforded Josh the opportunity to utilize two methods of further investigation. One was to trace the provenance and ownership records themselves through careful scrutiny of the what was written in these notes. The second was to utilize photogrammetry technology through the use of Ultraviolet photography to uncover the notes that had been chemically removed.

Ironically, the practice of chemical alteration that allowed forgery artists to mask provenance information and make fraudulent claims about texts also allows modern technology to most easily recover the information lost by erasure. The reaction of the erasure chemicals with ancient ink leaves a distinctive signature that can allow for easier modern recovery. What was state-of-the-art forgery technology in the 19th century is now the con’s greatest foil.

While chemical erasures are often invisible to the naked eye, ultraviolent photography is a simple, non-destructive process that makes textual recovery quite easy. For Josh, this involved working with Special Collections to capture images of the manuscript with a special camera lens in a darkroom. Light recorded by the raw images allowed them to then be artificially manipulated with post-processing techniques in Adobe Photoshop. The results were startling – at some point in the 19th century key provenance information about the book was erased.

With UV testing Josh was able to digitally recover accession numbers previously written onto individual works in the manuscript that had later been chemically scrubbed. The number that emerged from erasure did not correspond to any accession number listed in the afore-mentioned 1453 Padua library catalog. This ran counter to the information inscribed on the inner cover of Manuscript #4’s binding.

This raised new issues about the book’s authenticity. Was the entire book a fraud? Or, was it simply the provenance that was manipulated to make its origins more appealing than reality? Perhaps the book was in fact a potpourri of attractive Roman minor manuscripts of differing age that were collected and bound into a larger book to make it seem even more attractive. And who was the con artist that put it all together? As it turns out, Josh was able to address these issues with technology and careful scrutiny. Josh determined, “The book was made to look like it has one clean, unified history. It does not.”

Turning to the accession history gleaned from the inner cover Josh found that the manuscript had also appeared in an auction catalog written by a man named Guglielmo Libri in 1849. Guglielmo Libri Carucci dalla Sammaja (1803-1869) was an Italian count and mathematician who became infamous in the 19th century when he was prosecuted in France, in absentia, for the theft and forgery of over 30,000 ancient and historic manuscripts. Libri’s kleptomanic interest in manuscripts seems to have began with his time as a student and professor of mathematics. As an academic he developed an overly keen interest in owning original works written by great Renaissance and Enlightenment-era scientific masters. However, it was when Libri was appointed, rather ironically, to a secretarial position with the Committee for the General Catalog of Manuscripts in French Public Libraries in the 1840s that his career as a book thief really took off.

Libri was not merely gathering books for his own private collection. He was also interested in selling stolen books. One of Libri’s selling tactics involved mutilating—he called it ‘restoring’—manuscripts and collected works that had a low market value, then rebinding the mutilated pages into rearranged collected volumes. The effect was to bind more marketable texts alongside less valuable minor works to increase their sale price. This is precisely the case for Manuscript #4, being a collection of major works of Cicero especially popular in the Middle Ages, together with some lesser known works gaining popularity in the Renaissance.

Libri also used a team of Italian chemists, specialists in book repair, to mask his creations. Through chemical manipulation, more recent manuscripts were made to look older than they really were. To manipulate the book’s history Libri would consult the collection catalogues of Europe’s earlier libraries and ascribe accession numbers of actual books from the past to his new creations.

So much for certainty about the book as a product of Padua. As Josh says, “This is not the most outstanding manuscript in the world, that is, it’s not so extremely rare as to become a blockbuster. And so a more prosaic explanation for why Libri would go through this trouble is that he did steal it and that he is trying to disguise its provenance, so that no one could find him out.”

With closer scrutiny Josh was able to determine that some of the book’s inscriptions were suspicious. An inscription made and scrubbed by Libri on the front inside cover had been partially covered by a bookplate affixed by a later owner. Before the prior owner added his bookplate, Libri himself had also affixed a descriptive note describing the nearly erased inscription, which he himself had made and erased. With the bookplate eventually added, and Libri’s erased inscription obscured, later scholars and appraisers did not take notice of the small bits of erasure that were barely visible to the naked eye. When Kathleen Whalen later read the early note about the erasure, she looked to the back cover and found an additional, second erasure – unaware of the first. Thinking this second erasure was the one to which Libri referred to, she actually unwittingly revealed Libri’s chemical erasure.

This was the critical piece of evidence Josh needed. It would become the linchpin of his research. Again, through UV photography he was able to recover the lost inscription inside the back cover with a startling result: this rear-cover note referred to a completely different accession number and provenance. The recovered inscription states that the book belongs to the “abbey/abbot in Florence,” not, as the front inscription claimed, from a “monastery in Padua.”

And thus the book’s history branched out. Libri had taken part of another manuscript, had his chemist thoroughly efface the provenance information of one book, and assimilate this book to the older and disguise the whole package as a genuine manuscript from the Padua collection. The book’s pretense as a unified scribal text from Padua is therefore untenable.

The future of the manuscript is to be determined by Bryn Mawr’s Rare Book & Manuscripts arm of Special Collections. If possible, Josh notes that it would be of interest to try to pin down the biography of each section with a little more precision. This might entail further scrutiny with new technology available at Bryn Mawr in coordination with Marianne Weldon, Collections Manager of Special Collection’s Art and Artifact Collection. Special Collections has recently acquired new photogrammetry technology for analyzing objects using a process known as ‘Multi-band Imaging.’ Multi-band Imaging will allow for UV/visible florescence, a technique using special cameras and lenses that can single out specific wavelengths of light. The technique is known to work particularly well with recovering chemical erasures.

Manuscript #4 is not the only book stolen by Libri to have passed through the Special Collections of Tri-co colleges. In 2010, a letter from philosopher René Descartes to Father Marin Mersenne was returned to the Institute de France by Haverford College after similar questions of its origins led researchers to determine that the letter had once been stolen by the famed thief.

While the history of the composite texts within the book is now complicated by the revelation that it is partially a product of Libri’s “old book restoration,” the book obtains new interest given its interaction with such a well-known and infamous forger. Eric Pumroy intends to update the current records of Manuscript #4 with Josh’s thorough investigation, placing a copy of his paper along with the manuscript.

In Josh’s words: “If it is from the 15th century, in its original binding, etc. – we must decide what “it” actually was. In the 19th century what was popular—what was selling—was a pristine, clean, old, unified text where buyers could say ‘oh wow, this is nice. This is a window into the past. This is a text that shows us the works of scribes centuries ago.’ Yet at the end of the day the best we can say is that some parts of this manuscript come from Florence, some likely from elsewhere. A provenance less easy, less clean, but perhaps all the more interesting for it.”