Students Peer Into the Past Through Vintage Microscope Used by Trailblazing Scientist

Based on research published in 1905, Stevens is credited as being one of the first biologists to describe the chromosomal basis of sex. E. B. Wilson is also credited with making the same find that year.

The students used the more than 100-year-old microscope to get a closer look at the embryos of aphids (tiny insects), echoing Stevens’ research and Davis’ own.

At the time it was purchased, the German-manufactured microscope was top-of-the-line, but pales in comparison to today’s microscopes.

“We found the optics to be...sort of…challenging” says Davis. “It’s amazing what Stevens and other investigators of the period were able to observe with the tools they had.”

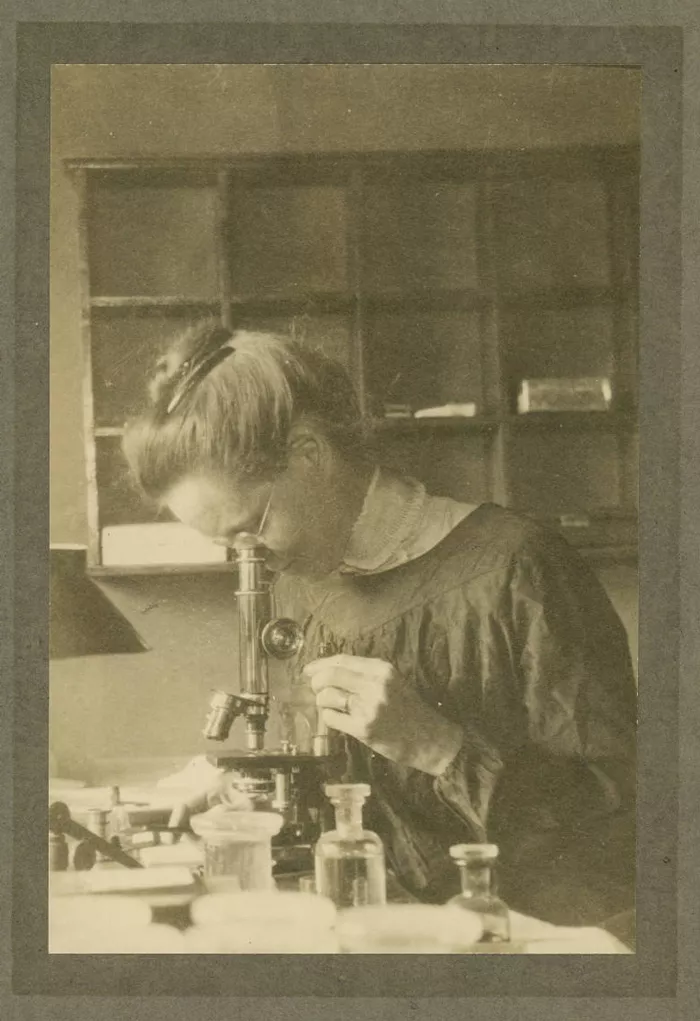

By coincidence, a recent Genetics Society of America profile of Stevens includes a 1909 photo from Bryn Mawr’s archives of Stevens working at the Stazione Zoologica in Naples, Italy, using a similar microscope. The article is titled Nettie Stevens: Sex chromosomes and sexism and is worth a read.

From the article:

At the time of her death in 1912, Nettie Maria Stevens was a biologist of enough repute to be eulogized in the journal Science by future Nobelist Thomas Hunt Morgan and for her passing to be noted in The New York Times. In 1910 she had been listed among 1,000 leading American “men of science.”

Yet in 1916, when Calvin Bridges published his proof that genes lie on chromosomes (the first paper in the first issue of GENETICS), Bridges cited the pioneering observations of a “Miss Stevens.” He also offered sincere thanks to “Dr. T.H. Morgan” and to his lab mates “Dr. A.H. Sturtevant and Dr. H.J. Muller.”

But “Miss Stevens” had in fact earned her PhD under Morgan’s supervision, just like Alfred Sturtevant, Hermann Muller, and Bridges himself. Why then did Bridges address the men as “Dr”, but granted Stevens only a “Miss”? The reason was likely convention. It seems to have been common in academic journals, including GENETICS, to refer to a woman with a PhD as “Miss” or “Mrs.” Indeed, Morgan’s obituary in Science is titled “The Scientific Work of Miss N.M. Stevens.”

Read the full article online.